A Duel of Gladiators

As COVID-19 keeps squash courts around the world under lock and key, we continue our look back at classic encounters from the British Open. This time, we revisit the 2018 quarter-final between Camille Serme of France and Welsh Wizard Tesni Evans. Serme entered the match as favourite, having beaten Evans in all six previous encounters. And while the underdog played some scintillating squash, it was the French player who ultimately claimed a captivating contest 3-2.

One aspect of this quarter-final which proved so intriguing was Serme and Evans’ differing playing styles. With a huge repertoire of strokes, Evans’ strength lies in her ability to vary her game. Serme, on the other hand, a more limited but physically superior player, would have known that the longer the match went on, the greater her chances of emerging victorious. Despite their differences, each style was in essence as effective as the other, with Serme claiming 52 points to Evans’ 51. Such a match-up prompted analogies from the commentary box of ancient gladiator fights, in which warriors of differing styles were paired for maximum intrigue and entertainment. We swap swords for racquets, Rome for Hull, and isolate five areas of this duel which warrant close investigation.

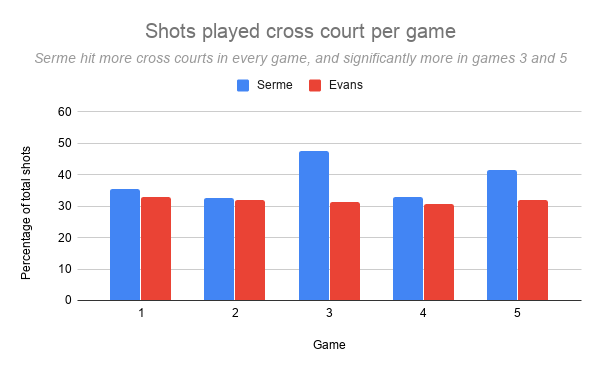

Evans steady, while Serme opts for cross court variation

One of the benefits of analysing sports in fine detail is that patterns emerge which challenge the accepted narrative. While commentators Lee Drew and Vanessa Atkinson isolated Evans’ balance between straight shots and cross courts as a key factor in her victory over Joelle King in the previous round–and predicted a similar approach on this occasion–it was actually Serme who employed such variation. Game to game, the French player oscillated enormously between the number of strokes she hit straight and the number she hit cross court, ranging from 32.7% of shots cross court in game 2 to an enormous 47.4% in game 3. Evans, on the other hand, was perhaps surprisingly a model of consistency in this metric, ranging only from 30.7% (game 4) to 32.8% (game 1).

Serme early intercept no problem for Evans – up to a point

Another area of play in which Serme and Evans differed was in intercept position. The more advanced a player’s intercept position–that is, the earlier they play the ball–the less time their opponent has between strokes. As a result, pushing up the court is a tactic often employed by players wishing to bring fitness to the fore; and Serme was no exception. Across the match, Serme hit 29.1% of her shots from the mid-court region, compared with Evans’ 24.1%, a pattern replicated in 4 of the 5 games. Evans averaged 66.0% of shots from deep on the court, while Serme hit 58.7% of her shots from this region.

However, because of these players’ different approaches, average intercept position per se was no great predictor of success: indeed, Serme lost the game in which she had her highest mid-court intercept index (34.7%, game 2). And with just a one point difference between the pair across the match, Evans’ deeper retrieval was not to her disadvantage: when the mid-court intercept difference stayed under 8%, the match was finely balanced.

But while the discrepancy in court positions in games 1-4 falls out of each player’s tactics, there is a point at which ceding the mid-court to your opponent too often–handing them control of tempo and the option to hit aggressively into all four corners–becomes unworkable. In the final game, Serme was able to hit 34.2% of shots from the mid-court region, compared with Evans’ 18.9%. Additionally, half of Serme’s shots were from deep, but Evans was by now hitting three-quarters of hers from behind the service boxes. It was no coincidence that game 5 saw Serme at her most dominant.

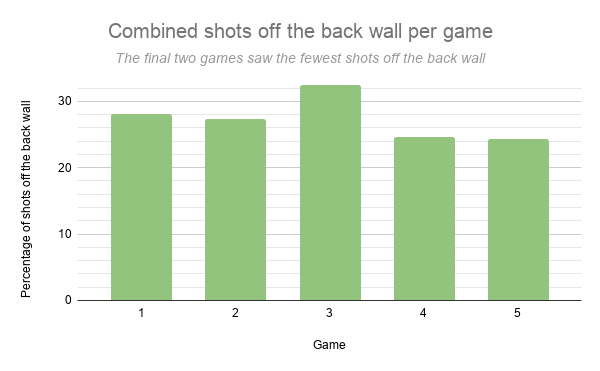

Evans uses back wall to her advantage

If Serme’s tactic was to keep the tempo high by pushing up the court, Evans’ riposte was to give herself more time. One way to slow the pace is to play shots late–once the ball has hit the back wall–and to make your opponent do the same. When Evans was at her most competitive, the percentage of ground strokes played off the back wall by both players was high: 28.1% in game 1, 27.4% in game 2, and 32.4% in game 3.

The final two games–both dominated by the French player–tell a different story. Game 4 saw only 24.6% of ground strokes come off the back wall, with a match low of 24.4% in game 5. Serme continued to press high and reduce Evans’ recovery time. And with Evans herself no longer able to slow the game, Serme’s victory was assured.

Serme shines in longer rallies

Given the French player’s superior fitness, it may come as a surprise to learn that the average length of rally won by each player was identical. The length of rally in those points won by Serme was on average 11.0 shots; when Evans won, this figure dropped fractionally to 10.8 shots. There was, however, a clear tendency for Serme to emerge victorious in the longer rallies: of the six completed rallies 25 strokes or longer, Serme won 5.

And while Serme’s generally superior mid-court figures were a reflection of different playing styles rather than dominance, the intercept position discrepancy between the players is worth noting in conjunction with longer rallies. In these longest rallies of the match, Serme was hitting an average of 4.8 shots from the mid-court region (31.9%); Evans, on the other hand, was hitting only 3.0 shots from this region on average (20.0%). This difference is reminiscent of the figures in game 5, and underscores the finding that Evans struggled on those points when this discrepancy became too large.

The conclusion is striking: while rally length and average intercept position on their own were no predictors of success, the combination of long rallies and early hitting was enormously advantageous to the French player.

Stamina and aggression: Serme’s tactics at loggerheads

As highlighted above, Serme’s tactics in this encounter–early intercepts, longer rallies, moving Evans across court–were based on the knowledge that the longer the match went on, the more likely her victory. An approach which often goes hand in hand with this line of attack is to limit your opponent’s so-called “easy” points–that is, your unforced errors–by reigning in the ultra-attacking shots. A corollary of reducing your error count by playing safer squash is your outright winner count also tends to decrease. You might expect a player looking to lengthen the tie as much as possible to score low in both error and winner count. In this contest? Not so.

Over the 5 games, Serme committed a total of 26 unforced errors. This figure is high in comparison with Evans’ impressively miserly 14. On the other hand, Serme hit a remarkable 38 winners (Evans 25), of which a mammoth 12 came in the first game alone. Such aggression from Serme, so often stretching the fine margins above the tin, was in keeping not with a physical player, but with a player looking to take fitness out of the equation.

After 5 games, 112 rallies and 72 minutes, Serme emerged victorious from the Yorkshire colosseum. The up-and-coming Wizard from Wales deserved plenty of credit for taking Serme the distance. But on rewatching, the French number one might have questioned, despite her victory, whether all her tactics were really pulling in the same direction.